Vanilla Grass’s ultimate writing resource on story plot structure.

Story Structure

If you’ve just begun to dip your toe into the world of creative writing, you may have come across the term “Story Structure.” You may have also encountered its cousin, “Story Arcs.” Or that cousin’s new wife, “Beat Sheet,” who appeared more recently but is always welcome.

While these terms can feel foreign, the good news is that they’re all simple enough to understand even for the most nascent writers. Story structure is also integral to how to write a great story, so learning the various methods is always a good use of your time.

And if there’s one thing every good writer knows, it’s that writing time is precious.

So, if you’d like, check out our table of contents for a specific story structure. Or you can minimize it and jump ahead to learn everything there is to know about how to structure your novel.

Warning: Examples in this post contain SPOILERS.

What is Story Structure?

Photo by Mian He on Unsplash

In short, story plot structure is the skeleton of your story. The bones are the crux of your characters and their journey. Or, if you prefer a more topographical analogy, story structure is the map that guides you as you write a book. Some people refer to setting up a story structure as “story mapping” for just this reason.

Story structure consists of how you start writing a book, how the protagonist (your main character or MC) and themes change in the middle, and where and how they come out the other end.

What Are the Different Types of Story Plot Structure?

If you’re wondering how many types of story plots there are, you’re not alone.

Academia also wondered, and has since come to terms with at least 6 (but more likely 7, or 9, or 36) basic plots for storytelling. The “how” of writing these stories is story plot structure and comes in just as many forms.

Some of the most popular methods for how to plot a story ( featured in our awesome plot mapping graph) include:

- Aristotle’s 2-part structure

- The 6 main story arcs

- The classic 3-Act Story

- The 4-Act Story

- Freytag’s 5-part Dramatic Structure (or Freytag’s Pyramid)

- Hauge’s 6-stage Story Plot Structure

- Dan Wells’ 7-point plot structure

- 15-point Beat Sheet from Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat”

As you will see, I’ve listed the story plot structure methods in order of complexity, least to most in-depth. This way you can see how they build on each other and work toward similar goals.

Aristotle’s Poetics Dramatic Story Structure

To start, who better than the philosopher Aristotle? And while he focused his analysis of story plot structure on tragedies, the principle works for all types of storytelling.

After analyzing various plays, Aristotle realized that a story isn’t just a bunch of different pieces thrown together. A story is one whole unit that works together. Simple enough, right? Basically, he’s saying that no part of a play or story should exist without the other parts.

Sound familiar?

It should. Because what Aristotle proposes in his work Poetics is basic cause and effect.

Nothing should happen in a story unless it has business being there. And no revelations, reversals, discoveries, or changes of heart should occur that aren’t first set up by a chain of events beforehand.

Carolyn Hoffert, www.vanillagrass.com

Taking it a step further, Aristotle proposed that this causal chain consisted of two major links (the beginning and end) filled with minor links. The first major link, or beginning of a story, he called the complication.

To use a metaphor, he related the complication of a story plot structure to the snarling of a knot. Each minor chain within this link works to build a growing problem that the protagonist must later undo.

Aristotle referred to the second major chain, or the ending, as the unraveling. This is when the protagonist smooths out the knot.

According to Aristotle, the complications or knot tying that occur should arise because of a significant flaw in the protagonist. Conversely, the resolution or untying of the knot should come from the protagonist overcoming this flaw. Unless, of course, the story you’re writing is a tragedy. In which case, the flaw should be his undoing and end the story in a true catastrophe.

So, there you have it, the most basic story plot structure you can use to write your book. Make a bunch of trouble for your protagonist (centered on their faults). Then resolve the trouble by helping your character get over themselves, or ending them tragically. Piece of cake!

If, however, you’re looking for a little more structure to turn your story into a great book, read on.

Who is Kurt Vonnegut?

The natural next step in this story structure journey is the 6 basic story arcs.

Kurt Vonnegut, author of Slaughterhouse-Five, first mused upon the shapes of story arcs in the 1940s when he wrote a (rejected) master’s thesis at the University of Chicago. Since then, the idea that different stories have similar story structures has become mainstream. These include stories like Cinderella and the rise of Christianity.

As Vonnegut explains in his lecture on the Shapes of Stories, he created a simple graphing module to map the shape of popular stories.

The X-axis represented story chronology (or the timeline of plot progression). And the Y-axis represented the fortune, or emotional journey, of the protagonist.

After putting in a broad array of popular stories (including some from the Bible), he compared them to each other.

That’s when Vonnegut concluded: “The shape of the curve is what matters.”

In other words:

The way the emotional journey of a character progresses through the story events is what makes a story successful.

Carolyn Hoffert — www.vanillagrass.com

What Are The 6 Main Story Arcs?

After Vonnegut turned the complex form of storytelling into digestible graphs (a method we, of course, love), a group of researchers from the University of Vermont and the University of Adelaide decided to take Vonnegut’s research a step farther in a 2016 study on the shapes of story arcs.

First, the researchers gathered 1,737 works of fiction from Project Gutenberg, the digital library. Then they ran them through a computer database to assess the primary story arc of each. And lastly, the computer algorithm graphed the crowdsourced emotional score of words within sections of a book. The happier the set of words (like laughter, happiness, love, joy, etc.), the higher the number on the y-axis. The sadder the words (death, pain, fear, terror, etc.) the lower the number.

They took the resulting graphs and concluded there were 6 primary story arcs the computer identified the most. And voila! The birth of the six main arcs in story plot structure!

So without further ado,

Story Structure: The 6 Main Story Arcs

Next, we will take a look at the 2016 study’s 6 Main Story Arcs.

First, we have:

1. The Steady Rise Story Arc (a.k.a Rags to Riches)

While the researchers who expanded on Vonnegut’s work liked to call this category “Rags to Riches,” the label can be confused with Charle’s Booker’s 2nd basic story plot type from his book “The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories.”

I’m therefore going to stick with calling this story arc The Steady Rise. But know that many rags to riches stories (though not all) fall under this category.

So, what goes into a Steady Rise story arc?

Examples of The Steady Rise Arc:

When you research rags to riches stories, the results can be a mixed bag of results. You get not-quite-matches–Cinderella, for instance, often gets misplaced here–Or stories no one has ever heard of.

Some of these more obscure stories include Dream, The Human Comedy, or the more obscure, The Ballad of Read Gaol.

So, here’s a more relevant list of The Steady Rise story examples:

- Anne of Green Gables

- Any Korean drama ever (See: Secret Garden, Boys Over Flowers, etc.)

- The Ugly Duckling

- My Fair Lady

- Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

- Will Smith’s The Pursuit of Happyness (which, incidentally, is based on a real rags to riches story about Chris Gardner).

For example, take a look at the graph above from the 2016 study. The Steady Rise story arc starts with the protagonist below their 50% emotional mark. In short, they begin the story unhappy but not utterly miserable. This is usually due to the protagonist’s humility, optimism, or another favorable trait.

Next, after a small dip in fortunes around the call to action, or inciting incident, the fortune of the protagonist steadily improves. This steady increase in emotional happiness, however, does not preclude them from minor ups and downs throughout the second act.

Lastly, the protagonist ends up much happier than when the story started. Their emotional story arc may dip a little at the end, depending on the circumstances, but overall the ending’s happy.

If you’re considering a sweet Steady Rise story arc for your novel, then take heart. This story arc is a favorite among readers and constituted about 1/5th of all the stories the researchers graphed out.

In the same vein, we have the next story arc:

2. The Steady Fall Story Arc (a.k.a. Riches to Rags)

As is easy to see in the graph above, The Steady Fall is just the opposite of The Steady Rise. These stories are usually tragedies and often come with some sobering social commentary.

Examples of The Steady Fall Arc:

- Romeo and Juliet

- Othello

- Hamlet (noticing a dismal Shakespeare trend?)

- Studio Ghibli’s The Grave of the Firefly

- 1984

The beginning of a Steady Fall Story begins near the top of the happiness threshold. Remember how The Steady Rise protagonist isn’t entirely miserable when the story begins because of their redeeming quality? Likewise, the protagonist in a Steady Fall story isn’t entirely happy at the start because of their negative quality. These qualities could include jealousy, greed, lust, etc..

In a tragedy, it is usually in trying to satisfy their selfish desires that the protagonist’s happiness begins to fall.

Next in the story comes the 2nd act (or 3rd act in a 4-act structure). Here, the protagonist experiences an advance in fortunes that gives them a taste of victory and encourages them to continue. Then, circumstances start to go terribly wrong. Their fortune or morale curve starts its steady decline.

And lastly, the story concludes with them far worse off than in the beginning. In othe words, the protagonist loses their fortune, love, or general happiness. Sometimes, the protagonist’s Steady Fall even ends in death.

Note, while Shakespeare is master at Tragedy, not all his tragedies fit The Steady Fall story arc. (Just like how Cinderella doesn’t fit The Steady Rise.) While they do end in the same place, that’s a basic story plot, not a story structure arc.

3. The Fall-Rise Story Arc (a.k.a. “The Man in a Hole”)

In regards to the 3rd arc, Vonnegut remarked that “people love [the Fall-Rise] story; they never get sick of it!”

To that point, I’d say it’s also a favorite of writers as well.

If you miniaturize the Fall-Rise arc into smaller segments, you can see it in every story, repeated over and over.

Vanilla Grass

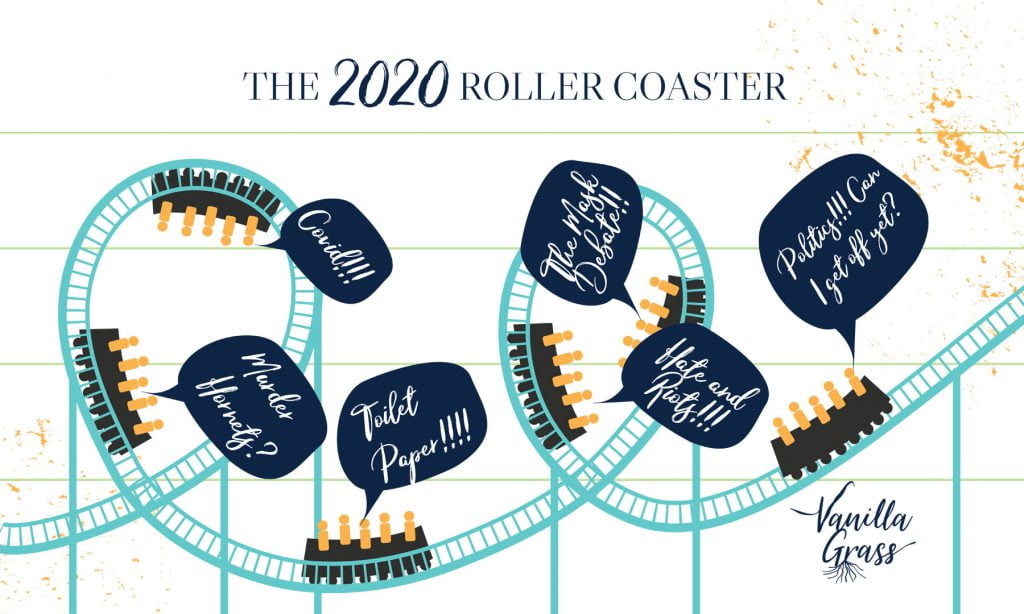

Does the incessant up and down of fortunes sound familiar? I dunno, like everyday life? Or try all of the year 2020. Let’s take a brief look at the similarities.

Fall-Rise Story Arc Examples

- How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days. (For you romance writers, most “boy meets girl” plots follow this storyline.)

- The Wizard of Oz

- Finding Nemo

- Moana

- Boss Baby or Shrek. (Comedies also tend to follow this curve.)

As you can see, the Fall-Rise story arc begins with the protagonist, well, falling. Where they start the fall depends on the basic plotline, but they’re typically above the 50% emotional/fortune threshold. Then, they take a swing at something, miss terribly, and end up in trouble.

The next act(s) involve the character continuing to fall until they hit the bottom where they have to try to climb their way out.

Finally, the character succeeds, making this a happy-ending story instead of a tragedy.

Again, most stories are littered with mini-examples of the Fall-Rise story arc. The protagonist hits snags in their journey (think classic adventure novel problems like getting lost, hurting feelings, getting attacked, etc.) and overcome them on their way to accomplishing their primary goal.

Many stories employ a double “man in a hole” story arc. The double dip in story arcs is perfectly acceptable (especially for books over 50,000 words or for plotlines that extend across several books in a series), just make sure that the second hole the protagonist falls in is much deeper and harder to get out of than the first!

4. The Rise-Fall Story Arc (a.k.a. the “Icarus” Story Arc)

Like it’s brother, The Steady Fall story arc, The Rise-Fall story arc ends in tragedy.

The Rise-Fall Story Arc Examples

- The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

- Icarus (obviously)

- Troy

- Braveheart

- Titanic

Now, if you’re not into writing tear-jerkers or otherwise bleak affairs, don’t disregard this arc! It can serve as a very important tool for writing satisfying stories, as I will mention in a second. But first, let’s go over the main elements in this story arc.

In the Rise-Fall story arc, the protagonist starts off discontent and wishing for more. Again, where the hero begins emotionally on this journey is up to the basic story plot, but generally, the protagonist’s emotional satisfaction sits below the 50% mark.

The middle of the book then sees them climbing toward their goal, getting oh-so-close, then falling back down.

The end of a Fall-Rise story arc? Tragedy. Tears. Maybe death. Definitely copious amounts of hair-pulling.

So why is this story arc important to the happy-ending novelist?

Because, aside from literary fiction that doesn’t follow traditional story structure guidelines, most stories have a villain. And when the hero is suffering on his downward arc, the villain is rising to the top of his. Conversely, when the hero swings up to a triumph, the villain fails and plummets. In other words,

In every Fall-Rise hero story, there’s a simultaneous Rise-Fall villain story taking place.

www.vanillagrass.com

So, while you’re checking to make sure your protagonist’s story arc is on track, you can use this graph to make sure your antagonist is taking the reader for an emotional journey as well.

5. The Rise-Fall-Rise Story Arc (a.k.a. The Cinderella Story Arc)

And here, at last, we see the beloved Cinderella story. Yes, she goes from rags to riches, but it’s not a steady rise. Instead, her journey is a turbulent roller coaster of emotion.

The first thing that happens in The Rise Fall Rise story arc is the protagonist sitting below the 50% emotional mark, hoping for more and generally being a good person.

The next part of the story involves the protagonist getting a glimpse of what they had hoped for, then losing it and feeling even lower than before. In Cinderella’s case, she meets her fairy godmother, makes it to the ball, falls in love, and then flees like a bat out of hell, leaving behind her slipper.

To conclude, the final part of The Rise-Fall-Rise story arc involves a sudden rush back to the top. For example, in Cinderella’s case, finding the other glass slipper and living happily ever after.

It’s important to note that in these stories, the meteoric rise at the end is often due to events outside of the protagonist’s control. Sometimes, this can result in a Deus ex Machina, or almighty power, that comes out of nowhere to redeem the character.

Other stories (and some may argue more satisfying ones), lay the groundwork for the miraculous save at the end, so it feels more natural.

Let’s take a look at The Rise-Fall-Rise story arc examples below.

The Rise-Fall-Rise Story Arc Examples

- Cinderella (the fairy godmother left her the other glass slipper)

- The Return of the King in The Lord of the Rings series (the eagles who come out of nowhere to save Frodo)

- Pinnochio (the blue fairy turns him into a real boy)

- Big Hero 6

- Any Marvel movie (note, the heroes in these stories usually earn their endings which contributes to their universal appeal)

6. The Fall-Rise-Fall Story Arc (a.k.a. The “Oedipus” Arc)

To conclude the list of the Six Main Story Arcs, we end with another tragedy. The Fall-Rise-Fall stories can often feel even more heartbreaking because they offer the reader a glimmer of hope in the middle of the story, only to snatch it away again at the end.

I’d say the most common place to find these story arcs is in the first book in a series. There has to be enough closure to leave the reader satisfied but also give them a reason to buy book 2, right?

Fall-Rise-Fall Story Arc Examples

- Red Queen (the 1st book in a set of 4) by Victoria Aveyard

- Oedipus (obviously)

- A shocking amount of Japanese short stories (especially involving Kitsune)

- Ender’s Game

To begin, The Fall-Rise-Fall story arc starts above the 50% fortune/emotional mark. The inciting incident that moves the story forward is often their search for carnal things (again, driven by greed, power, hubris, money, lust, etc.).

The middle of the story (2nd or 2nd and 3rd act) involves a sharp decline as they fail at their goal, then an upward struggle as they begin to find traction. Consequently, this segment usually ends with the protagonist hitting the highest point on their upward swing. They think they’re invincible and safe at last.

The final act in a Fall-Rise-Fall plot involves a sharp, painful descent much worse than the first one.

Now that you’ve read through the 6 main story arcs, you may be wondering, now what? How can I write a book using the story arcs? There’s so much more that goes into a story!

I agree.

So let’s look at how using more advanced story plot structures in combination with the main story arcs can help us write a great book.

The Classic 3-Act Story Plot Structure

As you may have noticed in some of the descriptions above, the 3-act story structure is a popular plot structure for writing great stories. It is also super easy to wrap your head around.

Act I:

The 1st act in a 3-act story structure involves the setup of a story and usually takes up NO MORE than the first 25% of the story. Some bold writers will even knock it out in one chapter.

The 1st act is where you describe your world, the characters in it, and your protagonist’s wants. The writing community often refers to this as the exposition.

Act I Example

In The Fellowship of the Ring in The Lord of the Ring series, this is when Frodo is running around as the whole village sets up for Bilbo’s birthday party. Life is simple, and Frodo is completely unaware that something far more wicked is about to come knocking.

The wicked thing that comes a-knocking is known as the inciting incident. While not always evil, the inciting incident is almost always unexpected.

An inciting incident is an external act that forces your character to take a step out of their ordinary. Some plot structures refer to this as “The Call.” This force should directly correlate to the “want” you set up for your protagonist in the first act.

www.vanillagrass.com

In Star Wars IV: A New Hope, the inciting incident is when the evil empire kills Luke’s uncle and aunt. With all his family dead, Luke is free to leave his familiar home to travel the universe. This change in fortunes also matches Luke’s want to leave Tatooine with his friends in the 1st act of the story.

Act II:

The 2nd act in a 3-act story structure involves what writers lovingly refer to as “the muddy middle.” This act is where the bulk of the action and turmoil happens and usually takes up AT LEAST 50% of the story.

Often, the pattern of this act follows the fall or rise of the chosen story arc. On a rising curve, the protagonist is going two steps forward one step back. On a falling curve, the protagonist is going one step forward and two steps back.

In contrast to the 6 main story arcs, the 2nd act in a 3-Act story structure looks more like a staircase than a gentle slope.

www.vanillagrass.com

Act II Example

Consider the ubiquitous Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. What happens between the inciting incident when Harry learns he’s a wizard and his climactic fight with Voldermort at the end? A LOT!

Act II is where the protagonist makes friends and enemies, learns new skills, and gains more fears. This act is also where the fun and games happen and where the heavy world-building takes place. The second act in a romance is also where the relationship draws closer and simultaneously falls apart.

The complexity of the 2nd Act is also why there are advanced plot structure methods. Sometimes writers need to break the gargantuan task of forming a story’s middle into more palatable chunks.

While the scope of Act II is unique to each story, it generally concludes in one way: a T-up to the climax or grand finale. In other words, the 2nd act goes out on an action high, with the readers on the edge of their seats waiting to see how the protagonist will handle the final challenge in the third and final act.

Check out this useful list of Act II examples, including everything from Hamlet to Tootsie.

Now on to the 3rd act.

Act III:

To start, the 3rd act in a three-act story structure involves the climax of a story and its rapid winding down to a happily ever (or never) after. It usually comprises NO MORE than the final 25% of the book. And some people believe the shorter, the better.

Consequently, this standard of brevity often correlates with word count.

The shorter the book, the smaller the percentage the ending should take up. Why do think so many children’s books wrap up with “And they lived happily ever after.”

www.vanillagrass.com

Therefore, in longer novels and in series, you can add endings that take longer. Or, like in the case of The Return of the King, you can add multiple endings that all take way too long (or maybe that’s just me). Still, it’s a classic! Rules are meant to be broken . . . ?

In a story arc that ends on a rise, the protagonist faces the ultimate obstacle and comes away triumphant. In contrast, a tragic story arc ends with a fall. The protagonist faces the final monster (hopefully both internally and externally) and fails.

In a 3-Act story structure, the 3rd act seals the protagonist’s fate.

Act III Examples

In happy ending books, the protagonist achieves the love, societal standing, peace, or shiny magical object they yearned for the whole book.

For example, see Sword in the Stone.

In a tragic ending, the protagonist fails to get what they want and loses everything else in the process.

For example, see The Boy in the Striped Pajamas.

Remember that the dramatic answer to the problem in Act II should be the opposite of the solution in Act III.

If the protagonist fails to accomplish their goal at the midpoint, they succeed at achieving it in the final act for a happily-ever-after ending. In a tragedy, whatever glimpse of hope they find in act II is forcibly taken away in act III.

The three-act story structure is popular among writers and story critics for its simplicity and ease in making a basic outline. If you’re looking for something more detailed to help you write a great book, then read on to some of the more complicated story structures I go over below.

The 4-Act Story Plot Structure

While bearing many similarities to the classic 3-Act structure, the 4-Act story structure breaks the middle act down into 2.

The idea of the 4-Act structure is to split the middle act at the midpoint and force the protagonist in a new direction, or what Aristotle calls a reversal.

Splitting a story at the midpoint helps create a stronger connection to the theme at the beginning and end of the story. Remember, the midpoint should be an echo of the protagonist’s want in Act 1 and a mirror of the choice he faces during the climax in the final act.

Examples of theme in a 4-Act Story Plot Structure

For examples of want and theme mirroring, read a romance. Any romance.

Take the classic, Pride and Prejudice, for instance. The midpoint occurs when Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy argue, he confesses his emotions (terribly), and she rejects him.

First, we see an echo of Elizabeth’s desire in the beginning—for someone to value her for who she is and not what she has—and Darcy’s failed response. Then, we see a mirror of the choice she will have to make in the end—whether or not she can stop acting like a hypocrite and allow herself to love Mr. Darcy despite his station and his failings.

Of course, these same correlations can be made in a 3-act story structure, but breaking the pieces of a story into 4 acts can help writers see the necessary benchmarks more clearly.

After the midpoint in Act II, Act III amps up the protagonist’s remorse at their failure. Act III also lays the groundwork of preparation needed to succeed in the climax.

Of course, while the 4-act story structure gives a little more direction than the classic 3-Act structure, writers seeking more guidance can look to the more complicated story structure methods below.

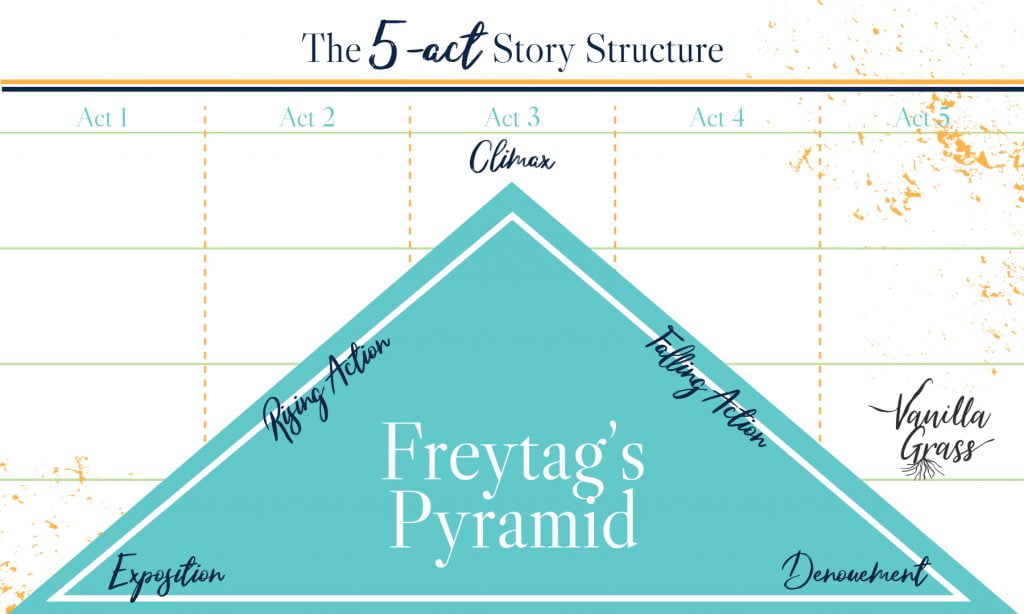

Having gone over 3-Act and 4-Act story structures, the 5-part dramatic structure devised by nineteenth-century Gustav Freytag is our next stop.

Unlike the 3-Act and 4-Act structures, the graph lines on Freytag’s pyramid relate to the overall action in the story, not the emotional journey of the protagonist.

As you can see in the graph above, Freytag’s dramatic structure looks very much like a triangle or pyramid. The shape is very fitting, not just in how the action in a story plays out, but because pyramids are sturdy shapes built on simple foundations.

So what is the foundation of Freytag’s 5-Act Story Structure?

Exposition

The Freytag Pyramid’s 1st act starts with exposition and getting the reader used to the world. It is in this act that the writer establishes the protagonist’s ordinary life and inner desire, or “want.”

Rising Action

Fretyage then refers to the 2nd act and part of the 3rd act as the “rising action.” The rising action includes all the problems that get in the protagonist’s way and looks like the 3-Act story structure’s staircase.

But the rising action can’t go on forever, which leads to the:

Climax

The Rising Action peaks at the climax in the 3rd act or midpoint. By this point in your story, all the foundation for the ending should be built. This includes the beginning theme and the mirror moment that reflects the protagonist’s choice at the end of the story.

And after the rise comes the—Fall. Or, according to Freytag’s Pyramid, the:

Falling Action

In other words, Act 4 is a quick descent in action where all the storylines come together, and Aristotle’s knot gets untangled.

Consequently, the falling action should solve the protagonist’s problems (usually through a trying ordeal) and see them through the other side.

To clarify, the concluding “other side” in stories is often referred to as the “new world” or “new normal” and occurs in the final act, or:

Resolution or Catastrophe

The final act, a.k.a. the resolution or catastrophe, is where the story settles, and we see how the character and world end up after all the changes that occurred.

Remember that the sharp ascent in Freytag’s 5-Act Story Plot Structure is tension and plot progression, not the character’s emotional arc. You could have your character swooping to despair as the rising action accelerates upward.

www.vanillagrass.com

Take Titanic, from our earlier list of Fall-Rise-Fall examples. After the set of scenes that lead to a steamy romance between the two main characters, the Titanic hits an iceberg.

Whoops.

What was a pleasant romp about the ship for the protagonists becomes a nightmare or sharp descent in their emotional story arc. People are betraying other people. Jealousy rears its ugly head. And, oh yeah, everyone is falling to their icy death. This uptick in chaos, however, is the rising line in Freytag’s Pyramid.

For reference, check out this chart below, where we combine The Fall-Rise-Fall story arc with Freytag’s 5-Act Story Structure.

As you can see, the climax points don’t line up if you follow each method’s recommended fall lines. This misalignment is okay, and one of the reasons that every writer has their preferred story structure for each book they write. Sometimes, one method just fits better than another.

Even so, you can see how the graphs offer a valuable perspective on how a story arc works within a chosen story structure. The lowest point in the first Fall nearly coincides with the Climax point in Freytag’s Pyramid. The highest point of the Rise arc also almost matches where the falling action finishes in the 5-Act story structure.

The main difference is the emotional arc. It makes sense that after all the action finishes in a tragedy, the emotional state of the character would plummet quickly. It is why Aristotle called the final act the Catastrophe, after all.

However, it’s okay to shift the arc or structure one way or the other to match up more closely, so you know where to place the events in your story. See the example below:

By moving up Freytag’s climax and lengthening it’s falling action, or denouement, to match the Fall-Rise-Fall story arc, the two data sets create a more cohesive story structure.

Michael Hauge’s 6-Stage Story Plot Structure

Are you starting to feel like a story structure guru? Great!

Next, we’re going to tackle the six-part story structure. Okay, it’s more like a 5-key turning point, 6-phase writing structure, but hang with me.

While so many points may sound like a lot upfront, Hauge himself assures that:

Not only are these turning points always the same; they always occupy the same positions in the story. So what happens at the 25% point of a 90-minute comedy will be identical to what happens at the same percentage of a three-hour epic.

Michael Hauge

In other words, if you learn this method and decide it works for you, you’ll never have to learn another one again, no matter what you write!

So, let’s jump in.

Stage 1: The Setup

Stage 1 in Hague’s 6-Stage writing structure is called “The Setup.” Sounds pretty par for the course, right? That’s because it is. If you can’t tell by now, all stories start with introducing the character and the world. It’s unavoidable, though execution can vary widely.

This stage takes up NO MORE than 10% of your story and must draw the reader into the initial setting. Cue establishing everyday life and identifying the protagonist’s sympathetic trait.

These sympathetic traits can range from positive attributes (remember Cinderella’s endearing optimism and kindness?), to being good at a skillset (hello, Katniss and her bow and arrow), to a situation that imbues empathy within the reader (enter orphan Annie).

In Finding Nemo, two stories are being told in one, which means two setups before two turning points. The first is for Marlin. The Setup is his happy-go-lucky self with the love of his life before tragedy strikes and changes him.

For the sake of Hauge’s six-stages and five-turning points, however, I’m going to focus on Nemo. The setup for little Nemo is his life with his dad in their anemone. The sympathetic trait? His gimpy fin and the fact that we know his mother died. We learn about his world, his relationship with his dad, and his aspirations of freedom.

In Ever After, there are also two setups. One that serves as more of a prologue/backstory and involves Danielle growing up happily with her father as they prepare for a new stepmother and stepsisters. The turning point for this would be her father dying suddenly. This is not the Setup and turning point that make the story, however, because we jump forward to where Danielle has already acclimated to her new life.

Then 2nd Setup occurs years in the future when Danielle is working on the farm as the day breaks over her significantly reduced situation as a servant instead of a family member.

Turning Point #1: The Opportunity

At the 10%(ish) mark in your story, an “Opportunity” presents itself to the protagonist. This turning point is similar to the inciting incident or “call” in other story structure methods. It creates a new desire in the protagonist or change in the world that propels the protagonist forward.

Do not be tricked by the positive connotation of the word “opportunity.” This change of fortune can be (and often is) very, very bad for the protagonist.

Don’t get caught up on making this the ultimate struggle. Remember, the “Opportunity” is just a hint of what’s to come in the midpoint and climax. For now, it just needs to get the hero moving.

In Finding Nemo, this occurs when Nemo chooses to defy his dad and touch the “butt.” Rebelling against his father is not Nemo’s main storyline, it just hints at the real storyline about him and his father learning to trust each other.

Or in Ever After, where two pieces make up The Opportunity. First, the Baroness sells off Danielle’s old family servant and friend. Second. Danielle knocks the prince off his horse with an apple, and he pays her to stay quiet about it. Romance-wise this also kicks things off between them as the meet-cute, though the prince doesn’t realize it until the end.

Getting her friend and fellow servant back does not need to be Danielle’s book-long mission; the Opportunity just needs to get her to the castle to meet the prince.

Stage II: The New Situation

In Stage 2, which comprises the next 15% or so of the story, the protagonist reacts to the opportunity. Very often, the opportunity pushes not only the story forward, but the location of the protagonist as well.

In Hauge’s Stage 2 of a story, the protagonist acclimates, plans for, or deals with the newness of their new situation.

Back to Nemo. The New Situation occurs after he touches the boat. Nemo is scooped up and taken to a fish tank in Sydney, Australia, where he spends the next few scenes meeting his tankmates and gathering information about the strange new world.

Or in Ever After. Danielle spends the next small chunk of story pulling out a fancy dress and feeling out of place on the castle grounds as she pretends to be a countess.

Turning Point #2: The Change of Plans

Ready for the next stage? First, we need to hit Turning Point #2, which happens at the 25% mark of the story. The 2nd turning point correlates to the end of Act 1 in the 3-Act and 4-Act story structures.

The Change of Plans turning point changes the protagonist’s desire (created during the Opportunity) into something more concrete and important.

Hauge’s Turning Point #2 changes the true desire of the character.

www.vanillagrass.com

In Finding Nemo, Nemo’s desires shift from wanting to rebel against his father, to acclimating to his new environment, to being determined to find his way back to the ocean. He and his tank mates make a plan to dirty the tank and escape through the sewers.

(Note: this is a dual story-line movie, so this moment feels like it occurs further into the story. But if you cut out Marlin’s journey, it lines up nicely.)

For Ever After, the Change of Plans occurs when the prince comes to call, sending Danielle in a flurry as she realizes she wants to keep the spark between her and the prince going instead of coming clean about who she really is or avoiding him altogether.

Stage III: Progress

Enter Stage 3, which lasts for the next 25% of the story. This stage is when the going gets good for stories with an uphill arc, or terribly for stories with a downhill arc.

Consequently, for Nemo, this is him getting stuck and losing his confidence on a downhill swing.

For Danielle in Ever After, this is her adorable date with the prince on an upward swing. They visit a monastery’s library, get lost, and have a spontaneous run-in with the gypsies.

The thing to remember with Hauge’s Progress stage is that the highs or lows will be short-lived because the protagonist’s fortunes are about to take a sharp turn.

Turning Point #3: The Point of No Return

You’ve been here before!

The Point of No Return coincides with the 3-Act and 4-Act structure’s midpoint!

At the 50% mark in the novel, the protagonist reaches a point where they commit fully to a new goal (not knowing, of course, that their fortunes are about to turn for the worse).

For Nemo, the third turning point is when Nigel the pelican tells Nemo his father is traversing the ocean looking for him. His father’s courage gives Nemo the gumption he needs to go through the filter the second time, overcoming his fear of getting sucked to his doom after the first time’s terrifying ordeal.

In Ever After, Turning Point #3 culminates in Danielle giving in to her feelings and kissing Prince Henry at the end of their date. The turning point solidifies further when Danielle talks back to the Baroness.

She feels high on life and hopeful that there’s something more in her future than eternal servitude to her witch of a step-mother. So, she rebels and burns any remaining goodwill between her and her captors. She’s cruelly whipped, and Prince Henry declares his love for her.

Stage IV: Complications and Higher Stakes

Of course, if everything went the way the protagonist wanted, the story would be rather dull. Instead, for the next 25% of the novel, you get to torture your protagonist!

In Hauge’s Stage IV or Complications and Higher Stakes, the goal the protagonist recently committed to 100% begins to slip farther and farther out of reach. Life becomes more difficult, and what the protagonist might lose or gain becomes so much more important.

For Nemo, this is when their escape plan fails, and the dreaded Darla shows up to take him home. (Cue screechy violin music).

In Ever After, this is when Danielle breaks free from the cellar her step-mother threw her in and goes to the ball to tell Henry the truth. While this may seem like the climax, for the Rise-Fall-Rise Story Arc classic to Cinderella, Stage IV occurs while the character is still tumbling down to their dark moment.

Turning Point #4: The Major Setback

The Major Setback is also commonly known as the “all is lost” moment. It occurs at the 75% mark in a story.

During the Major Setback, it must appear to the protagonist that all hope is lost, and the sun will never shine again.

Hauge’s Major Setback must leave the protagonist with only one option: one last do-or-die effort to reach their goal.

www.vanillagrass.com

For Nemo, this turning point takes place around the same time his father shows up and sees him dead.

Yikes.

But that’s not Nemo’s all is lost moment, that’s his father’s. Nemo’s major setback comes after his heartbroken father leaves. Nemo goes down the drain after him. He pops up lost in murky waters where he is scooped up in a giant fishing net right before reaching his father.

In Ever After, the Major Setback comes when Prince Henry (brutally) rejects Danielle. The Baroness then tells Danielle she never loved her before selling her off to cringe-worthy Monsieur Le Pieu.

While some may argue that Danielle’s dark moment in the cellar is the “all is lost moment,” or Major Setback at Turning Point #4, this is the true “all is lost” moment. Even though Danielle being trapped in the cellar and having doubts about their relationship did present a setback, Danielle still had so much more to lose. Cue the true “all is lost” moment here:

Stage V: The Final Push

The Final Push is the protagonist’s rally! It’s when they pick themselves up by their bootstraps and use everything they have left. During this push, the protagonist must make the final play for their goal and be prepared to lose everything trying.

www.vanillagrass.com

In Finding Nemo, the Final Push ties back to Nemo’s transformed desire from earlier to trust his father and have his father trust him. The Final Push manifests in Nemo’s new self-confidence and motivation to save the tuna he’s trapped with inside the nets. If his plan fails, he risks his father’s judgment and distrust and could potentially die.

In Ever After, Danielle makes her Final Push when she stops caring about how much other people value her and values herself enough to win her freedom from La Pieu.

Turning Point #5: The Climax

For Hauge, this takes up most of what would be the 3rd act in a 3-Act story structure or the 4th act in a 4-Act story structure. He suggests aiming for the last 90-99% of the story.

According to Hauge, three criteria make a great climactic moment work.

- The protagonist must face the most significant obstacle of the entire story.

- The protagonist must determine their own fate.

- The protagonist’s choices must resolve the external motivation that drove the story once and for all.

For Nemo, the Climax comes when he has to convince his father to trust him enough to save the tuna. The Climax resolves when his father agrees to help him, solidifying their trust in one another and saving the tuna.

This moment meets Hauge’s three criteria for a satisfying climax.

First, Nemo faces his biggest challenge because his life and thousands of others hinge on whether he can overcome the problem he had at the beginning of the story.

Second, Nemo takes fate into his own hands and helps the tuna even though he doesn’t have to.

Third, Nemo and his dad physically reuniting and learning to trust each other ends the outer motivation that drove the story.

In Ever After, the climax comes after Danielle saves herself from slavery, and Prince Henry shows up to beg forgiveness, which Danielle chooses to accept.

Note here that Danielle’s plummet in circumstances followed by an abrupt upswing in fortune matches the Rise-Fall-Rise Story Arc classic to Cinderella perfectly. It also is a more satisfying ending because Danielle earns her salvation instead of having it magically dropped in her lap.

This climax also fulfills Hauge’s three criteria for a proper story Climax.

First, Danielle faces having to forgive the judgment (and utter humiliation) she’s been fighting the whole book by accepting Henry’s apology.

Second, she decides her fate because the prince is at her mercy and not the other way around.

And third, the external motivation that drove the story is resolved because she is finally free from the oppression of her step-mother and society’s constraints on what makes a person valuable.

Stage VI: The Aftermath

Even if a story’s Climax is super-satisfying and hits all the necessary criteria, there are usually still some loose ends to tie up (or smooth out according to Aristotle).

Hauge’s Stage VI: The Aftermath includes all the feel-good moments (or sobby tear-jerker ones in tragedies) that give the reader satisfaction and a sense of completion and resolve.

In Finding Nemo, this is the scene where Nemo and his dad are back home on the reef with the new friends they both made along the way, their newfound sense of adventure, and complete trust in one another.

In Ever After, this is where we get to see all the good things! First, the Baroness and her one wretched daughter get what they deserve by having to bow to Danielle and work as servants. And second, Danielle gets what she deserves by marrying the prince and bringing her one nice sister and farmboy friend into the good life with her.

Phew! It can be a lot to process, but when you break it down over some of the other plots, you’ll see that it’s just a more detailed explanation of the simpler 3-Act and 4-Act structures.

Now we’re ready for Dan Wells’ 7-point Plot Structure.

Dan Wells’ 7-Point Story Plot Structure

With Michael Hauge’s Six-Stage Story Structure under your belt, Dan Wells’ 7-Point Plot Structure will come easy.

Instead of Phases and Turning Points, Wells uses Pinch Points and Plot Turns. Let’s take a look.

Opening Image or Hook

Same old, same old, right? Just like all the other story structure methods, Wells starts with an opening scene or sequence of the story that creates empathy with the main character. He suggests you aim for the .025 mark of your book, or the first tenth of your first quarter. For those trying to figure out the percentage in your head, this is the 2.5% mark in your book.

Similar to Hauge’s need for a sympathetic trait, Wells encourages writers to create empathy for their protagonist by showing how they lack for something.

For Wells’ 7-Point Plot Structure, I’m going to use Disney’s highly underrated Tangled.

In Tangled, Rapunzel lacks a family that loves her. We know this by how poorly her fake mother treats her and her tragic backstory.

Establish the world? Check. Create empathy? Check.

Plot Turn #1 or Inciting Incident

Next is Plot Turn #1, which should occur by the 20% (1/5th) mark of your book. Here, you should introduce conflict and give your protagonist the “Call to Adventure.”

The opening conflict and the Inciting Incident in Dan Wells’ 7-point Plot Structure are two separate but connected pieces of Plot Turn #1. They build on each other like Aristotle’s links to drive the character forward.

www.vanillagrass.com

In Rapunzel’s case, the conflict that builds from the beginning is two-fold.

- Rapunzel wants to be free to leave her prison but her mother stands in the way.

- Flynn Rider wants to be free to live in ease but poverty and rules stand in his way.

These 2 points manifest in Rapunzel fighting with her witch mother and Flynn breaking the law.

Dan Wells’ Plot Turn #1 occurs when two sets of growing conflict clash together to make the inciting incident. The result? A problem that forces the protagonist forward.

When Flynn Rider shows up in Rapunzel’s home (to be knocked out by a frying pan), Disney has already set up the first storm of conflict, and the protagonist is rearing to go.

So, what should be the result of Wells’ first plot point?

The End of the Beginning. Just as Hauge’s Turning Point #1 leads to Stage II’s New Situation, Well’s first plot point should end with the protagonist experiencing new ideas, new people, and new secrets.

In the 3-Act and 4-Act story structures, this marks the end of Act 1.

Pinch Point #1 or Apply Pressure

Well’s 1st Pinch Point should come between the 25-35% (around the ⅓) mark of the story.

I do love that Wells calls these moments “pinch” points because it’s a good reminder that whatever happens in the story should stretch, hurt, or otherwise make your protagonist miserable.

These are not fun points for your protagonist (unless you’re writing a Steady Riise romantic novelette). They are growth points.

The best way to pinch your protagonist and apply pressure is by having something go terribly wrong. Try attacking your protagonist with bad guys, forcing your character to tell a lie, introducing your villain, or causing a calamity.

Once your inciting incident has occurred, every pinch point going forward should continue to force your hero to act.

www.vanillagrass.com

In Tangled, the first pinch point comes at The Snuggly Duckling.

At this quaintly thuggish bar, Rapunzel overcomes her uneasiness, wins over some criminal hearts, and then faces the guards chasing after Flynn. In Wells’ terms, this would be the ‘bad guys’ attacking since they’re on opposite sides. Fighting and running from the castle guards also force Rapunzel and Flynn to act, which then ends them in a flooding cave.

And dying in the cave, Rapunzel enters the:

Midpoint

The Midpoint should happen around the 50% (½) point in your novel. Some questions to ask at the midpoint are:

- How and why are the characters still doomed to fail?

- Or, how is the character’s former identity getting in their way?

At the Midpoint, you need to highlight the imperfections and false truths the protagonist believes and how they’re affecting their progression.

www.vanillagrass.com

Because no protagonist starts out perfect, right? (With maybe an exception for ultimate hero types who change the world and not themselves, like Captain America.)

Once you’ve asked those questions, the protagonist needs to move from reaction to action and from one place to another (usually emotionally AND physically).

In Tangled, the midpoint occurs when Rapunzel and Flynn—now Eugene—share their intimate secrets in the flooding cave, have their lovely moment falling in love amidst the lanterns, and make a choice in the camp outside of the city.

Rapunzel’s choice comes when Gothel, her fake mother, shows up in camp and tries to take her home. Rapunzel refuses, going from running and hiding from her fake mother to openly defying her. From reaction to action.

Pinch Point #2 or Crisis

In Dan Wells’ 2nd pinch point, we get to cause more trouble for our characters. This point of character growth should occur around the 60-75% mark on your story arc.

Pinch Point #2 is one of those one step forward two step back situations if their emotional arc is on a downswing, or two steps forward one step back situations if their emotional arc is on a downswing.

In terms of similarity, Pinch Point #2 relates closely to Hauge’s Turning Point #4 or Major Setback.

In other words, things go very, very badly for the protagonist. Their plan fails. Their beloved mentor or friend dies. The bad guys appear to be winning hard. And the protagonist feels helpless in the jaws of defeat.

During Wells’ Pinch Point #2 or Crisis, there should be significant questioning of motives and many “Why me!?” moments.

For our dear Rapunzel, this comes when Gothel ties Flynn/Eugene up and sends him to be captured with the crown while convincing Rapunzel that he chose to leave her. She’s heartbroken. He’s facing a death sentence. And they are both seriously regretting their life choices.

Plot Turn #2 or Climax

Wells’ Plot Turn #2 should come around the 75% (¾) mark in the story.

In the external story arc (or things happening to the protagonist), the events of the Climax should trigger the protagonist’s fear about themselves and the world.

In the internal story arc (or realizations going on inside the protagonist), the protagonist should be realizing or learning things about themselves to help them overcome the fear or trigger presented.

Plot Turn #2 is similar to Hauge’s Stage V, or Final Push. The protagonist should rise to the occasion, feel like they’ve got the power to succeed, and use that empowerment to snatch victory from those previously mentioned jaws of defeat.

In Tangled, this is when Rapunzel realizes she’s the missing princess, and Flynn/Eugene realizes he loves Rapunzel. When Flynn shows up to save Rapunzel, she learns he didn’t betray her and realizes she loves him too. She gives her freedom up for him, then he, in true romantic grand gesture style, gives his life for hers.

Like, for reals, why does Frozen get more love than this movie?

Final Image or Resolution

Dan Wells’ Final Image is the housekeeping of a novel and should take place between the climax and the story’s end.

Usually, this means the last 10% of the book OR LESS.

According to Dan Wells, the resolution should show how the protagonist has achieved internal and external equilibrium. How their identity matches the real truth instead of the false truth they started with. And how the protagonist followed through on the promise made at the midpoint.

By the Resolution of a book, the protagonist should be the opposite of who he was at the hook of the story.

www.vanillagrass.com

The two main exceptions to this are the ultimate hero story and the tragedy.

For a Captain America or ultimate hero story, the character should remain the same, having changed the world instead.

For a tragedy, the character is usually worse off, and the world is just as cruel as ever.

To finish up our Tangled example, Rapunzel’s resolution comes when she reunites with her royal parents. She and Flynn/Eugene decide to get married in their happily ever after.

Rapunzel got to see the floating lights, Mother Time caught up with Mother Gothel’s dusty old bones, and Rapunzel stopped believing Gothel’s lies that she wasn’t lovable. Our smoldering Flynn embraces the Eugene side of himself and realizes that his dream was love, not money.

Perfection.

Now that we have Dan Wells’ 7-Point Plot Structure under our belts, we’ll take a look at Blake Snyder’s 15-Point Beat Sheet.

But first:

What is a Writing Beat? And What Does it Have to do with Story Plot Structure?

While there are many niche definitions of what a “beat” is, especially in the screenwriting world, we will focus only on one.

For simplicity, a writing beat is a moment within your story where something happens (or doesn’t). These beats build on each other to form scenes, which form chapters, which form books.

So, if the structure of a novel is the bones of your story and the emotional arc is the heart, the beats are the cells that form together to make the body – bones and heart included.

Without beats, there is no story.

A beat could be the moment a character feels love for another. Or the anger at being told what to do. A beat could even be the breath a character takes after almost drowning. They’re the little micro-feelings and events that make up everything in life.

What Is a Beat Sheet?

A beat sheet, then, is a list of the necessary moments your protagonist needs to have to move from point A to point B. Some people make beat sheets for each chapter, while others go bigger and less specific and make a beat sheet for the entire book.

Which takes us to the 15-Point Beat Sheet, or a map of beats your protagonist should follow to get from the beginning of the book to the end.

Blake Snyder’s 15-Point Beat Sheet

Snyder wrote the book, Save the Cat!, a best seller for over 15 years, to help screenwriters write amazing scripts. So what does screenwriting have to do with writing a book?

They both tell stories.

And the writing community as a whole recognizes the benefit of incorporating story beats into writing to create great books.

So, what are the beats in Snyder’s Beat Sheet?

Snyder’s 1st Beat: Opening Image

Have the urge to skim ahead?

I feel ya! That’s because no matter what you do, the story has to establish the world the protagonist lives in and the norms they experience. There’s simply no way around it.

If you don’t write an opening image, your readers will form an impression of one on their own, so it’s best to write your opening image intentionally and well.

www.vanillagrass.com

Especially since the first five pages of a novel are crucial for maintaining readership!

This beat should be short and sweet and give a snapshot to the reader of the main character’s problem before all the adventure begins. For perspective, the opening image is your first page and NO MORE than your first chapter.

Snyder’s 2nd Beat: Set-up

Snyder recommends you follow up on the 1st beat by presenting the protagonist’s world as it is, their standing within it, and what they’re missing from their life. This 2nd beat is that sympathetic trait Hauge and Wells mention as well.

Note: The establishment of your character is just as necessary and important as the hook!

WARNING! Hearing something once is an accident (Hauge), twice a coincidence (Wells), but three times means you better pay attention (Snyder)! If your reader can’t relate to your character, they WILL stop reading!

Snyder’s 3rd Beat: Theme Stated

To best cover Snyder’s Theme Stated beat, let’s continue the metaphor of beats being the cells that make up the story. Sometimes these cells can overlap or exist in the same space.

Snyder’s Theme Stated beat involves conveying your story’s universal truth or message. I’m not asking you to go all didactic on people, and neither is Snyder, but having a theme in your novel that speaks to everyone is necessary for readers to relate to and love the story.

And this can be done without sounding preachy or Aesop’s fables-y. You can have another character hint at the truth to the protagonist (who doesn’t understand the significance yet). Or you can show examples of the theme or its opposite in the world around the protagonist.

An impactful story weaves the theme into all the other beats of the story. And it first rears its head around Snyder’s second beat or the Set-Up.

With this in mind, the order of the Theme Stated beat and the Set-up beat are often interchanged in the order they’re listed. But since the theme occurs within the Set-up, I’ve listed the Set-up first.

Snyder’s 4th Beat: Catalyst

The Catalyst is Snyder’s interpretation of the Inciting Incident, the “Call,” or “The Opportunity” we have seen in earlier story structure methods.

The Catalyst is the moment when the protagonist’s life irrevocably changes. Some examples Snyder gives are a fateful telegram, catching a loved one cheating, a monster sneaking (or worse, being allowed) on a ship, a moment of true love, etc.

It doesn’t matter what the Catalyst of a story is. All that matters is that the protagonist can’t go back no matter how much they wish they could.

www.vanillagrass.com

The “before” or “Thesis” world is no more, and change cannot be stopped.

Snyder’s 5th Beat: Debate

The Debate beat is another brief moment or set of brief moments that pop up as the story progresses. The 5th beat first appears after the Catalyst and centers heavily on self-doubt or uncertainty.

The questions to have your character ask themselves during this beat include:

- Can I face this challenge?

- Do I have what it takes?

- Should I turn back?

- Should I flee?

These are the moments and feelings the protagonist will have to overcome as they near the climax of the story. In a tragedy, these are the questions that eat away at the character until they give in to their fears. And fear can only lead to failure.

On that bright note, we move to Snyder’s 6th story beat and transition from Act 1 into Act 2.

Snyder’s 6th Beat: Break Into Two (Choosing Act Two)

After all the hemming and hawing and shoe-scuffing the protagonist does at the end of Act 1, they now must make a decision. Do they keep going or turn back? Do they choose to fight the monster or run away like a coward?

Whatever they decide, they move into the next act, or what Snyder calls the upside-down, “opposite world.”

The Break Into Two beat is similar to Hauge’s Stage II, or The New Situation. The protagonist is adapting, learning, and living with the choice they made.

Which leads to Beat 7.

Snyder’s 7th Beat: B Story

The B Story beat is another one of those amorphous, along-for-the-ride beats that coexist with their more definable brothers.

In many books, this is the “love story” that weaves itself into the workings of whatever is going on. Romance is a popular B-story and the reason we include the option to add it over a main plot in our awesome plot graphing calculator.

That said, it is not the only B story around. Intrigue, friend dynamics, secrets, lies, political struggles, war, and murder are some of the many B stories that can take place alongside your A story.

B stories involve side characters and plots that relate to the end but aren’t crucial to its outcome.

www.vanillagrass.com

Think Hermione and Ron’s love story in Harry Potter, or Frodo and Sam’s bromance in The Lord of the Rings. Or what about Inigo Montoya’s pursuit of the 6-fingered man in The Princess Bride?

All of these B stories add depth and interest to the story but aren’t vital to the success of the protagonist (though their support contributes to the ultimate outcome).

When adding B stories, it is essential to remember that the length and age of the audience of a book matter. A 40,000-word middle-grade novel may only have 1 or 2 subplots, while an adult fantasy that extends for 20 books may have a kajillion.

Yeah, I said KAJILLION. You go read Brandon Sanderson and tell me this isn’t true.

And on to Beat 8.

Snyder’s 8th Beat: The Promise of the Premise or Fun and Games

Fairly self-explanatory, the Promise of the Premise beat is when you, as the writer, deliver on the promise you made to the reader. This beat is also known as the “fun and games” section of the story.

Now let’s talk about what that actually means.

Readers choose books based on genre, length, familiarity with the author, the book’s summary, and let’s be honest, the cover.

But much more goes into why people keep reading a great book.

Readers choose to keep reading books because of the promise the author makes.

Story Promise Examples

For stories with an emotional arc that curves up to the midpoint, this promise includes:

- Follow-through on the theme hinted at in the Set-Up.

- Exploration of the new world the protagonist is thrown into at the Break Into Two.

- Fulfillment of the promised relationships growing closer together.

For an arc swooping down to the midpoint, the promise involves the same elements, just with the taste of bitter tears.

- Following through on a cutting, depressing, or otherwise bleak theme of failure.

- The exploration of the world where the protagonist gets lost and scratched up and misplaces his left shoe. The world turns out oppressive and bleak.

- Watching the lovers or friends quarrel.

When this beat falls on the “Man in a Hole’s” descending emotional arc, the fall down should be torturously brutal.

If you’re genre writing, make sure to incorporate some expected tropes. No sci-fi reader wants to read stuffy regency lovers dancing around their first kiss. And no romance reader wants to read a massacre.

Snyder’s 9th Beat: The Midpoint

While these story structure birthers (can I call 3 men that?) differ on what they call their various phases and pinch points and beats, the midpoint stays pretty consistent.

Why change what’s working?

Now, remember those story arcs we’ve been riding like a roller coaster? The midpoint of a story is the apex of the arc, whether it comes on a high or low. Snyder refers to this beat as either being “great” or “awful.”

Simple enough.

The beats that make up a “great” moment include (premature) feelings of triumph, satisfaction, love, contentment, etc. Basically, the protagonist is living the dream.

The beats that make up an “awful” moment, however, include despair, frustration, loneliness, hopelessness, and any other depressing words a writer can think of to impose upon their protagonist.

Snyder guides the reader a bit more on what this could look like by using the terms “False-Victory” and “False-Defeat.”

So,

What is a False Victory? What is a False Defeat?

In a False Defeat, the character who was previously high on life now feels like they lost all they worked toward. Their hopes are dimming further into black, and their pet dog died to boot. What they don’t know is that this is short-lived, and they will soon be back on track. Otherwise, it would be the end of a very tragic story.

In contrast, protagonists on an upswinging arc at the midpoint are more likely to experience a false victory.

A false victory is a win that gives premature confidence to the character and makes them too sure of their success and full of the dreaded hubris.

www.vanillagrass.com

A false victory could also include a victory at a heavy cost. At the midpoint in the book Uprooted, by Naomi Novik, the king and his guards charge into the forest to kill some evil sap-spilling trees. The trees absolutely trounce the king and his men, but they do manage to make it out alive with the object of their desire.

A victory? Technically, but at a substantial cost of personnel and morale. To top it off, the object they acquired wasn’t quite what they had hoped. Evil magic is tricky like that.

Few things in life ever last, am I right? And so we move on to the 10th beat.

Snyder’s 10th Beat: Bad Guys Close In

As far as titles go, this one is as clear as they come. But that doesn’t mean this beat will be the same in every story.

Indeed, there are many types of “bad guys” from which a writer can choose. You could go classic: scar-faced thugs with dark clothing and dirty mouths. Or you could go psychological: doubt, jealousy, fear, betrayal. Or, if you’d like, you could hit up nature: twisters, floods, the wandering mind of old age.

Whatever it is, the encounter will start to turn the protagonist’s fortunes around with 2 story arc exceptions. The Steady Rise and Steady Fall will only dip a small amount one way or the other but otherwise hold their course.

Bad Guys Close In Example

In Disney’s Hercules, this comes when he finally starts beating the monsters. Hades sends all the bad guys he has at him but Herc is on a roll.

Most importantly, Snyder’s 10th beat mirrors Well’s Crisis Point and Hauge’s Complications Stage. The Bad Guys Closing In should be a shadow of the true challenge coming in act three. A trial run, if you’d like, to see how the character will fare in the end. (Hint: the protagonist is never ready for what’s about to come in the final act.)

Which takes us to:

Snyder’s 11th Beat: All is Lost

Wherever your curve was at the midpoint, it should be the opposite of that now. With that in mind, the name “all is lost” can be a bit misleading.

If emotional arc’s on an upswing, the 11th beat could be another false-victory in the hopes of an alliance, a change in weather, or even a party invite.

But since stories include more happy-endings than tear-jerking tragedies, the “all is lost” label fits nicely. The character is in the throes of their trial and is wont to find a way out.

It is these dark moments that make great stories relatable. We, as readers, seek ourselves in the stories we read. And, with very few, questionable exceptions, we have all faced bitter moments of confusion where we tried our best and inevitably failed.

Without great struggle, there is no great victory. Or to go back to one of the oldest stories in the human cannon, without knowing evil, we cannot know good.

Which translates nicely into beat 12.

Snyder’s 12th Beat: Dark Night of the Soul

The Dark Night of the Soul is another beat nestled like one Russian doll into another. It is very similar to the Debate Beat in that it has the character questioning themselves, their quest, and their purpose in this world.

Like Snyder’s Debate Beat, the Dark Night of the Soul comes on the heels of hardship and propels the character forward into the next act.

Some questions to have your protagonist ask themselves at this beat include:

- Why me?

- (The classic and age-old) Why hast thou forsaken me?

- How did I get here?

- What went wrong?

- Why should I go on?

This moment of despair is what those struggling with addiction call “rock bottom.” There is nowhere to go but death or up. And, unless this is a tragedy, up goes the protagonist with the next beat.

Snyder’s 13th Beat: Break Into Three (Choosing Act Three)

After the appropriate (or sometimes prolonged) amount of wallowing and gnashing of teeth, the protagonist finds what they need to move forward.

This moment of renewed hope could include:

- Advice from a trusted advisor (who ironically usually dies during the Dark Night of the Soul)

- Encouragement from a B Story love interest or friendship

- A new tool or weapon

- A stroke of inspiration

- A realization about themselves or the world

- Sheer divine intervention (think the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio fixing his lie-filled nose)

- Or even a good, ol’ slap in the face

Whatever plot-moving device you choose, good stories will make sure they follow the Theme established back in the Set-Up and magnify it in the upcoming climax.

Which leads us to:

Snyder’s 14th Beat: Finale

The Finale is where the theme comes full circle.

www.vanillagrass.com

Whatever the protagonist didn’t comprehend in the beginning, they understand now. Whichever character trait they were lacking, they’ve now gained. And the personality fault that previously slowed them down is abolished or turned into a strength.

The exception to this, of course, are tragedies. Just give the protagonist the opposite of a happily-ever-after outcome. They lose everything they desired and even some things they already had (money, love, social standing, family, and sometimes even life).

The themes for tragedies are often commentaries on the vices of man, so whatever the protagonist loses in a tragedy should reflect the established theme. If the protagonist spurned his family for fortune only to realize they were why he succeeded, then losing them would be most appropriate. If the character had a sizable fortune but followed greed for more, then losing his fortune is most appropriate.

How the protagonist loses or gains everything is also vitally important in the Finale and should follow the established theme. The more closely the story beats align the stated theme, the higher the reader’s satisfaction.

Once you’ve played up the theme and had the protagonist overcome or succumb to their challenges, you’re ready for the next beat on Snyder’s Beat Sheet.

Snyder’s 15th Beat: Final Image

The Final Image beat, much like the Opening Image, gives the reader a brief but lasting impression.

Remember how the importance of the Opening Image Beat is to give the reader a glimpse of the “old world”?

The purpose of the Final Image Beat is to give the reader a glimpse of the protagonist’s “new world” and how far they’ve come.

It’s just as important to craft this scene with care as it is to craft the first scene.

The first few pages of a book keep the reader reading. The ending of a book is what makes the reader come back for your next book and recommend you to their friends.

www.vanillagrass.com

You don’t want to leave a bad taste in their mouth, not when word of mouth marketing is so important!

And that’s it for Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat beats. If you’ve read through all the different structures, you’ll see that they all follow similar lines, some just allow more room for improvisation and others give more structures for those writers who like to line everything up.

That leads us to an important question:

Which Story Plot Structure Should I Use to Write My Book?

Or, which story structure is best for my book?

That depends largely on what you’re looking for.

Best Story Plot Structure for Plotters

If you’re a natural plotter and want to be able to drop a bunch of detailed plot points into a chart and have the outline of a story finished, Michael Hauge’s 6-Phase 5 Point plot structure or Blake Snyder’s Fifteen-Point Beat Sheet might work better for you.

Pair it with your desired story arc in our plot graphing calculator and get writing!

Best Story Plot Structure for Pantsers

If you’re a free-spirited panster, on the other hand, and want to work with a more general idea of the story shape and emotional flow of the characters, then sticking with the looser 3-Act and 4-Act story structures is a better fit for you.

Just match it up with the intended story arc, pick your desired genre and tropes, and start writing a great book!

And remember: Always, always keep writing!

Carolyn

What’s your preferred story structure? Story arc? Or did we leave out an amazing plot tool you can’t live without? Make sure to tell us in the comments below! We love hearing from you!

Want more? Make sure to check out our plot calculator and free downloads for everything you need to start writing a great book. Or take a look at our writing conferences calendar so you can find your writing community.

Wow! This is a wealth of great info. Great resources! Thank you!

Thanks, Tara!

We’re glad you enjoyed the resources. We always love it when amazing authors drop in. 🙂

I was reading through some of your articles on this website and I think this internet site is really informative! Keep on posting.

Thank you for reading through the site! We’re happy you find the content useful.

But Marvel movies are no longer pop culture events. Now they feel like pop culture obligations. We see them because they re the closest thing we have to a nationally unifying story.

Great selection of modern and classic books waiting to be discovered. All free and available in most ereader formats. download free books

whoah this blog is wonderful i really like reading your articles. Keep up the great paintings! You realize, a lot of people are hunting round for this info, you could help them greatly.

Thanks for your post. I’ve been thinking about writing a very comparable post over the last couple of weeks, I’ll probably keep it short and sweet and link to this instead if thats cool. Thanks.

Absolutely! Glad it was helpful.

This is such a great resource! Thanks for doing this work!!